Zacharias Wagenaer: Patterns From The Past

2021-07-10 | Karen Jennings

As humans, we are always looking for patterns. They help us to understand the world and to make sense of events or behaviour on a large scale. However, sometimes patterns can lead us towards something more subtle, something that, however small, can tell us a little bit more about a person and the way in which they engage with the world. This subtle pattern-recognition is something that is quite common, though not exclusive, in historical research. It is one of the ways in which we can breathe life into a long-dead individual. For example, I have been reading a lot about Zacharias Wagenaer (also Wagener and Wagner) recently. Not only was he second commander of the Cape, after Jan van Riebeeck, but he lived an interesting and multi-faceted life, travelling the globe in a variety of capacities. Today I will focus on only one of those facets – his artistic talent – and how it influenced the trajectory of his career to a greater or lesser extent.

Wagenaer was born in 1614 in Dresden-Neustadt in present-day Germany. His father was a portrait painter and perhaps taught the young Wagenaer some of what he knew. By the time Zacharias reached the age of 18 or 19 and needed to be thinking about his own future, there were very few opportunities available to him. The Thirty Years War had decimated much of the surrounds and the economy was suffering. So, with his parents’ permission – as he is clear to point out in his autobiography – young Wagenaer set off for Amsterdam, where he began working for the famous mapmaker and publisher Willem Blaeu as an illustrator of maps. It is worth recognising that Blaeu is unlikely to have employed the young man unless he had some skill and talent.

After a year of copying the outlines of far-distant places and feasting his eyes on images of exotic creatures and objects, Wagenaer seems to have gotten itchy feet and wished to go in search of adventure of his own. He writes in his autobiography that Blaeu encouraged him to join the Dutch West India Company (WIC), and he soon signed on as a common solider and set sail for Dutch Brazil. Once arrived in Pernambuco, it was not long before his fine penmanship – a much sought-after skill, especially in a place where the death rate was so high – saw him promoted to a clerk. A few years later he was taken into the service of the new (and only) governor-general of Dutch Brazil, Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen. Maurits, since known as the humanist prince, had brought with him a cohort of painters and scientists to record the marvels of the new world. It is little wonder then that Wagenaer, with his artistic background and with so much stimulation around him, went on to produce his own drawings and descriptions of the flora and fauna of Brazil in his Tier Buch.

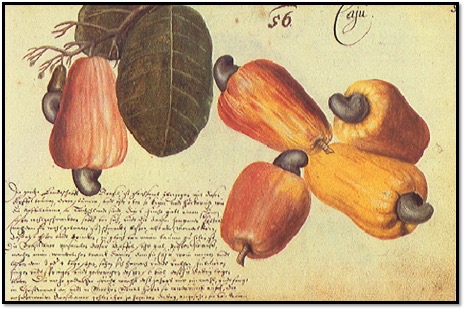

Painting and description of caju (cashew fruit) – note where the cashew nut grows on the fruit.

After seven years in the employ of the WIC, Wagenaer returned home, but the quiet life was not for him and within a few months he had signed on with the VOC, making his way to Batavia where he worked once more as a map designer. At the age of 34 a tactical marriage to a much older and influential widow saw Wagenaer promoted to junior merchant. He travelled on various missions around the East Indies, including to Canton as head of a trade embassy, attempting, amongst other things, to enhance the trade in Chinese porcelain, which was much desired in Europe. Unfortunately, the mission was a failure. Nevertheless, he made enough of a name for himself to be promoted to head merchant or opperhoofd of the Dutch factory at Deshima, Japan in 1657 and 1659. Here he played a central role in encouraging the Japanese to imitate, as closely as possible, Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, providing them with samples sent from Batavia. In fact, with all his years of experience as a draughtsman, Wagenaer even designed his own pattern – “silver tendril work on a blue ground”. But he complains in his daghregister (journal) that unsolicited imitations of an inferior quality soon overwhelmed the market stalls of Japan – items produced at speed by individuals hoping to take advantage of the demand for such goods. As a result, Wagenaer bought none of these initial Chinese replicas, nor those of his own design, for export to Europe.

An example of the type of blue-and-white porcelain that was being produced by the Chinese and that the Dutch would have wanted the Japanese to try and imitate.

By the time he reached the Cape as commander in 1662, Wagenaer had developed a great knowledge and enthusiasm for the art of ceramics and ceramic design. Moreover, he had grown accustomed to the wealth and associated luxury of the East Indies. It was a devastating blow when he arrived in the Cape, having intended to live a peaceful life there in semi-retirement, to discover that the rudimentary colony was short of food, was constantly ransacked by the Cape’s violent storms, that there was no glass in the window frames, and no decorations on the walls. This last, for a visual person, must have been hard to accept and he wrote to Batavia, requesting that pictures be sent at once. None came. There was also no pottery of any kind (other than that produced by the indigenous people, which the Dutch did not deign to use), and he wrote once more to Batavia, speaking of his shame when visitors landed at the Cape and had to look upon the VOC employees eating from shells or with their hands. He requested that skilled potters be sent, or if that could not be done, then at the very least some coarse pottery. Almost three years after his arrival at the Cape, on 26 September 1665, Wagenaer records in his daghregister: "This morning, for the first time, diverse kinds of baked and glazed earthenware were taken from the oven in the new pottery and found to be very good. Some were sold this afternoon on the public market, and a considerable quantity kept back for the next market day."

It is also likely due to his own efforts that a shipment of 185 pieces of Persian ware was sent from Batavia in late 1666. Unfortunately, Wagenaer was not there to receive it when it arrived at the Cape. He had recently returned to Batavia as a result of ill health. No doubt his successors dined off it for some time, though Persian ware is brittle and easily damaged, cracking if in contact with boiling water.

Example of what the Persian ware set in 1666 might have looked like.

This cursorily sketched pattern that runs through the life of Wagenaer allows us to trace the ways in which his artistic skills stood him in good stead throughout his 35-year career in the WIC and VOC. It brought him into the periphery of the world of travel and trade through his initial work on maps, which then inspired him to set off and participate in that world himself. The years to come saw his talents allowing him to engage with and record the flora and fauna of a land that was unknown to him. Later, he was able to influence fashions in porcelain design and assist in encouraging trade in Japanese porcelain. At a more practical level, his interest in ceramics saw the daily lives of soldiers and free burghers at the Cape improve by making pottery available to them when it had not been before. Much of this influence has been forgotten by now and Wagenaer is unlikely to ever be listed amongst the ‘big names’ of VOC history. Yet, what would I not give for an item of his own porcelain design to be discovered. No doubt there is an ancient, cracked plate somewhere, or fragments waiting in the ground. The hope is that these can one day be unearthed, that his simple design, of which he had been so proud and which had so disappointed him through the inferior imitations, can be added to the pattern of his artistic life.

References

-

S.C. Jordan, ‘Coarse Earthenware at the Dutch Colonial Cape of Good Hope, South Africa: A History of Local Production and Typology of Products’, International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 4.2 (2000), 113-143.

-

C.S. Woodward, Oriental Ceramics at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1795 (Cape Town: A.A. Balkema, 1974).

-

K. Zandvliet, ‘Zacharias Wagenaer 1614-1668. A Life in the Service of the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company’, in Oranda Higashi-Indo Kaisha: Deshimashokan-sho Wahe-varu-ten. The Dutch East India Company in the 17th century: Life and Work of Zacharias Wagenaer 1614-1668 (Nagasaki: Nagasaki Holland Village, 1987), 20-35.